Something I ran across while converting JsonSchema.Net from synchronous to asynchronous is that the “try” method pattern doesn’t work in an async context. This post explores the pattern and attempts to explain what happens when we try make the method async.

What is the “try” method pattern?

We’ve all seen various TryParse() methods. In .Net, they’re on pretty much any data type that has a natural representation as a string, typically numbers, dates, and other simple types.

When we want to parse that string into the type, we might go for a static parsing method which returns the parsed value. For example,

1

static int Parse(string s) { /* ... */ }

The trouble with these methods is that they throw exceptions when the string doesn’t represent the type we want. If we don’t want the exception, we could wrap the Parse() call in a try/catch, but that will incur exception handling costs that we’d like to avoid.

The answer is to use another static method that has a slightly different form:

1

static bool TryParse(string s, out int i) { /* ... */ }

Here, the return value is a success indicator, and the parsed value is passed as an out parameter. If the parse was unsuccessful, the value in the out parameter can’t be trusted (it will still have a value, though, usually the default for the type).

Ideally, this method does more than just wrapping

Parse()in a try/catch for you. Instead, it should reimplemented the parsing logic to not throw an exception in the first place. However, callingTryParse()fromParse()and throwing on a failure is the ideal setup for this pair of methods if you want to re-use logic.

This pattern is very common for parsing, but it can be used for other operations as well. For example, JsonPointer.Net uses this pattern for evaluating JsonNode instances because of .Net’s decision to unify .Net-null and JSON-null. There needs to be a distinction between “the value doesn’t exist” and “the value was found and is null,” and a .TryEvaluate() method allows this.

Why would I need to make this pattern async?

As I mentioned in the intro, I came across this when I was converting JsonSchema.Net to async. Specifically, the data keyword implementation uses a set of resolvers to locate the data that is being referenced. Those resolvers implement an interface that defines a .TryResolve() method.

1

bool TryResolve(EvaluationContext context, out JsonNode? node);

I have a resolver for JSON Pointers, Relative JSON Pointers, and URIs. Since the entire point of this change was to make URI resolution async, I now have to make this “try” method async.

Let’s make the pattern async

To make any method support async calls, its return type needs to be a Task. In the case of .TryParse() it needs to return Task<bool>.

1

Task<bool> TryResolve(EvaluationContext context, out JsonNode? node);

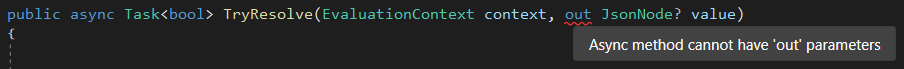

No problems yet. Let’s go to one of the resolvers and tag it with async so that we can use await for the resolution calls.

Oh… that’s not going to work.

Since we can’t have out parameters for async methods, we have two options:

- Implement the method without using

asyncandawait. - Get the value out another way.

I went with the second solution.

1

async Task<(bool, JsonNode?)> TryResolve(EvaluationContext context) { /* ... */ }

This works perfectly fine: it gives a success output and a value output. Hooray for tuples in .Net!

Later, I started thinking about why out parameters are forbidden in async methods.

Why are out parameters forbidden in async methods?

Without going into too much detail, when you have an async method, the compiler is actually doing a few transformations for you. Specifically it has to transform your method that looks like it’s returning a bool into one that returns a Task<bool>.

This async method

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

async Task<bool> SomeAsyncMethod()

{

// some stuff

await AnotherAsyncMethod();

// some other stuff

return true;

}

essentially becomes

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Task<bool> SomeAsyncMethod()

{

// some stuff

return Task.Run(AnotherAsyncMethod)

.ContinueWith(result =>

{

// some other stuff

return true;

});

}

There are a few other changes and optimizations that happen, but this is the general idea.

So when we add an out parameter,

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Task<bool> SomeAsyncMethod(out int value)

{

// some stuff

return Task.Run(AnotherAsyncMethod)

.ContinueWith(result =>

{

// some other stuff

return true;

});

}

it needs to be set before the method returns. That means it can only be set as part of // some stuff. But in the async version, it’s not apparent that value has to be set before anything awaits, so they just forbid having the out parameter in async methods altogether.

In the context of my .TryResolve() method, I’d have to set the out parameter before I fetch the URI content, but I can’t do that because the URI content is what goes in the out parameter.

Given this new information, it seems the first option of implementing the async method without async/await really isn’t an option.

A new pattern

While I found musing over the consequences of out parameters in async methods interesting, I think the more significant outcome from this experience is finding a new version of the “try” pattern.

1

2

3

4

Task<(bool, ResultType)> TrySomethingAsync(InputType input)

{

// ...

}

It’s probably a pretty niche need, but I hope having this in your toolbox helps you at some point.

If you like the work I put out, and would like to help ensure that I keep it up, please consider becoming a sponsor!